ANTHROPOLOGY OF MOTHERHOOD

MCDONOUGH MUSEUM OF ART

IN MEMORIAM

AL BRIGHT, MICHAEL J. WALUSIS & JACK CARLTON

JUNE 11, 2021 - JULY 24, 2021

525 WICK AVENUE, YOUNGSTOWN, OH 44502

OPENING CELEBRATION

JUNE 11, 2021 | 6- 8 PM EDT

ARTISTS

Amy Bowman-McElhone, PhD, curator

Fran Flaherty, Founder and Curator

Ada Bosonetto Schwerin, aom studio manager

Sara Tang, Digital Content Curator

AND THE

ART

“CARE PARADIGM”

Nicaragua, Korea, Peru, Afghanistan, Joyce Kozloff and Fran Flaherty, 2020

The Anthropology of Motherhood: Culture of Care exhibition features works of art that engage in the complex visual, material, emotional, corporeal, and lived experiences of motherhood, caregiving, parenting, nurturing, and maternal labor. AOM: Culture of Care presents a slate of artists that embrace the labor of care as “right and rewarding work.” Through video, sculpture, painting, and photography, the works presented address maternal identities with birth as a metaphor for regeneration, creation and renewal.

When Fran Flaherty curated the first Anthropology of Motherhood exhibition in 2014 for the Three Rivers Arts Festival, she did not anticipate how startlingly vital and relevant such an endeavor would be amidst a global pandemic in 2020. Yet, Fran’s beautifully radical exhibition, which is centered on the idea that societies should lead through gestures of care, provides a necessary grounding and reorientation during this unsettling time. While the show was originally produced as an aesthetic experience for nursing mothers functioning also as a space for respite and community, it has grown into a broader exploration of care-giving.

The culture or paradigm of care can be understood as an “ethics of responsibility for the other rooted in love and the material practices of care” that works to denaturalize negligence and violence as assumptions that drive social understanding. In a 2014 article for The Atlantic, Anne-Marie Slaughter, President of the New America Foundation, describes the care paradigm as an acknowledgment and facilitation of interdependence. Human beings cannot survive alone therefore we must care for one another. Slaughter calls for us to refocus our pursuit of happiness from competition and financial success to a social infrastructure that gives equal importance to competition and caregiving.

In many societies, the unpaid labor of care is largely taken up by women. The global pandemic of 2020 has made this over looked face highly visible, whether it is revealed in the tending to children while in quarantine, caring for isolated older relatives, providing sustenance as essential workers in grocery stores, or working on the front lines in hospitals as healing professionals, women bear the brunt. Postcolonial scholars Cho Haejoang and Ueno Chizuko seek to de-gender notions of care stating, “the labor of caring can no longer be designated the work of women…cannot any longer be free labor, nor can it be the cheapest kind of labor…Some people are already living a politics of care that views the condition of depending on others neither as a form of humiliation nor an invisible sacrifice, but as a right and rewarding work.” With these ideas in mind, AOM, Culture of Care presents a slate of artists that embrace the labor of care as “right and rewarding work.” Through video, sculpture, painting, and photography, the works presented address maternal identities with birth as a metaphor for regeneration, creation and renewal. In perfect symmetry, Fran welcomed her first grandchild during this pandemic. And so, in the midst of chaos and pain, life continues and flourishes through the labor of love and care.

The Anthropology of Motherhood: Culture of Care is on view at the McDonough Museum of Art after a successful virtual exhibition at the Pittsburgh Three Rivers Arts Festival and an in-person exhibition at Carlow University Art Gallery.

— Amy Bowman-McElhone, PhD

— Fran Flaherty, Founder, Anthropology of Motherhood

ANTHROPOLOGY OF MOTHERHOOD

CULTURE OF CARE

Please Be Advised

This exhibition attends to the bodily experiences of motherhood and caregiving, which are often stigmatized in Western culture. As such, there is imagery that represents female reproductive anatomies, childbirth, breastfeeding, and the experience, both spiritual and corporeal, of a mastectomy.

It is the undertaking of this exhibition and gallery to facilitate a space for dialogue, conversation, and discourse in order to countervail social injustices, including but not limited to the stigmatization, objectification, and marginalization of women. Embodying our mission of social justice, this exhibition foregrounds the lived experience and visual representation of motherhoods, caregiving, and the ethics of care.

Breast, Emily Paige Armstrong

Oil on Canvas, 8 1/2 x 11 in, 2020

"Breast" is part of a series of ten oil paintings entitled "Features and Figures" which were created to celebrate the female form. Each piece is painted with a delicate hand in pastel colors onto found glass picture frames. The style of each painting as well as the sturdiness of the found frame symbolizes the strength and beauty of every body. This particular piece is featuring a single breast painted onto a 8 &1/2 inch by 11 inch found frame, in hopes of assuring the viewer that every feature and figure of their body is beautiful just as they are.

Watermelons Are Not Strawberries, Sandra Bacchi

Archival Pigment Ink Prints, 2014-2018

“When I couldn’t eat strawberries, I pretended watermelons were strawberries.”

— 5 year old Vitória Bacchi to a friend who also had multiple food allergies

In WATERMELONS ARE NOT STRAWBERRIES I seek to better understand myself and to increase my awareness of how I react to challenges related to my experiences as a mother. The work is a blend of conceptual and documentary photography that reveals the shapes, textures and shadows of my love for motherhood as it merges with a lifetime of my own personal anxiety. The work grows into a story of resilience, perseverance, hope, and mutual support.My two daughters were challenged with severe food allergies and learning difficulties in their early years. In helping them to cope with their adversities, I was forced to delve into my own dark places to confront the deeply entrenched fear, shame, and guilt that stem from my then-undiagnosed dyslexia and celiac disease.

Food allergies and learning differences were the starting point of my journey in challenging my fears to be different. Once I let go of the rules and expectations I created for myself, which were not working for my daughters, the whole family dynamic changed. I didn’t want them to feel the constant neurotic need to fit into the social norms, as I did my whole life. We established our own “normal” way to live our lives, creating a sense of complicity, understanding, and empathy among each other, building a stronger relationship. In the beginning, it was a lonely path focused on trying to adapt and adjust my expectations of parenting. It turned into a life journey and artistic inquiry as I traced a connection between my childhood and my daughters' childhood.

Dyslexia, ADHD, food allergies and celiac disease are all connected through families’ DNA. Therefore, while I was advocating for my girls, I learned how to advocate for myself. While I was trying to understand my daughters, I deeply understood myself.

Untitled, Joyce Bowie Scott

Oil monoprint on homemade paper, 30 x 40 in, 2014

Monument, Crystal Ann Brown

Multimedia 3D Sculpture, 2019

Brown’s work has focused on holistically blending art and life. This blending of her studio practice with her daily life also touches on its inherent challenges. In her words, “my love/hate relationship with my kitchen might manifest in my drawings and paintings that celebrate work and the labor of love with a hint of fury and frustration shown in the economy of line found in blind contour drawings.” Her practice strives to reveal the underappreciated aspects of mothering and everyday life through the use of textiles, sculpture, time-based media, social practice and drawing.

The Nurturing Language, David Call

Lithographic Print, 12 x 18 in, 2019

American Woman

Mother and Godmother

Digital print, acrylic, and ink, 2019

*not available to view online

Deities, Tara Fay

Digital Print, 2020

Once I became a mother, I became more attuned to womanhood, and what a divine power creating life is. I view mothers as Goddesses and supreme beings, and with these photos, part of a series called 'Deity's', I wanted to represent divine status, and create imagery that is evokes Mother Goddesses and fertility, with colors and symbolism that represent both Oshun and Hera. The images of my daughters and I, with both staged and candid elements, represent the temporary nature of time, my offerings to them as their mother and protector, and my own sexuality.

Welcome to My Party, Valerie George

Welcome to My Party is an ongoing body of work culled directly from the artist’s experience of the diagnosis of breast cancer. Utilizing the aesthetics of 17th century Dutch still life painting, she wakes up to face the camera documenting her spirit in flux, and the transformation of her body.

The Light is for Me, Valerie George

Silver gelatin print, 1998

This photograph was taken of Artie Missey Brown just before her death. She was a supporter of George’s choice to become an artist and was often the muse and model for her photographs.

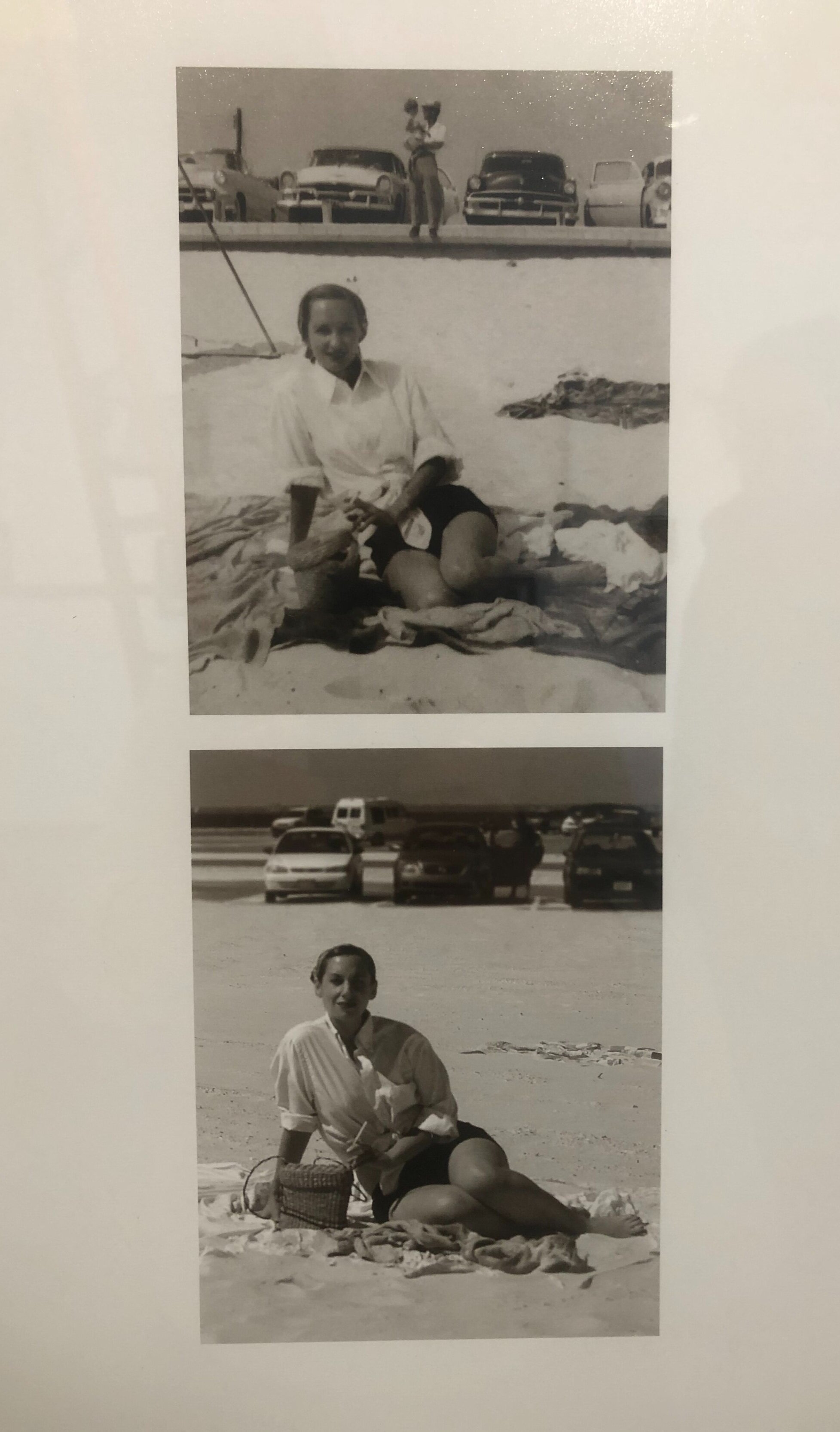

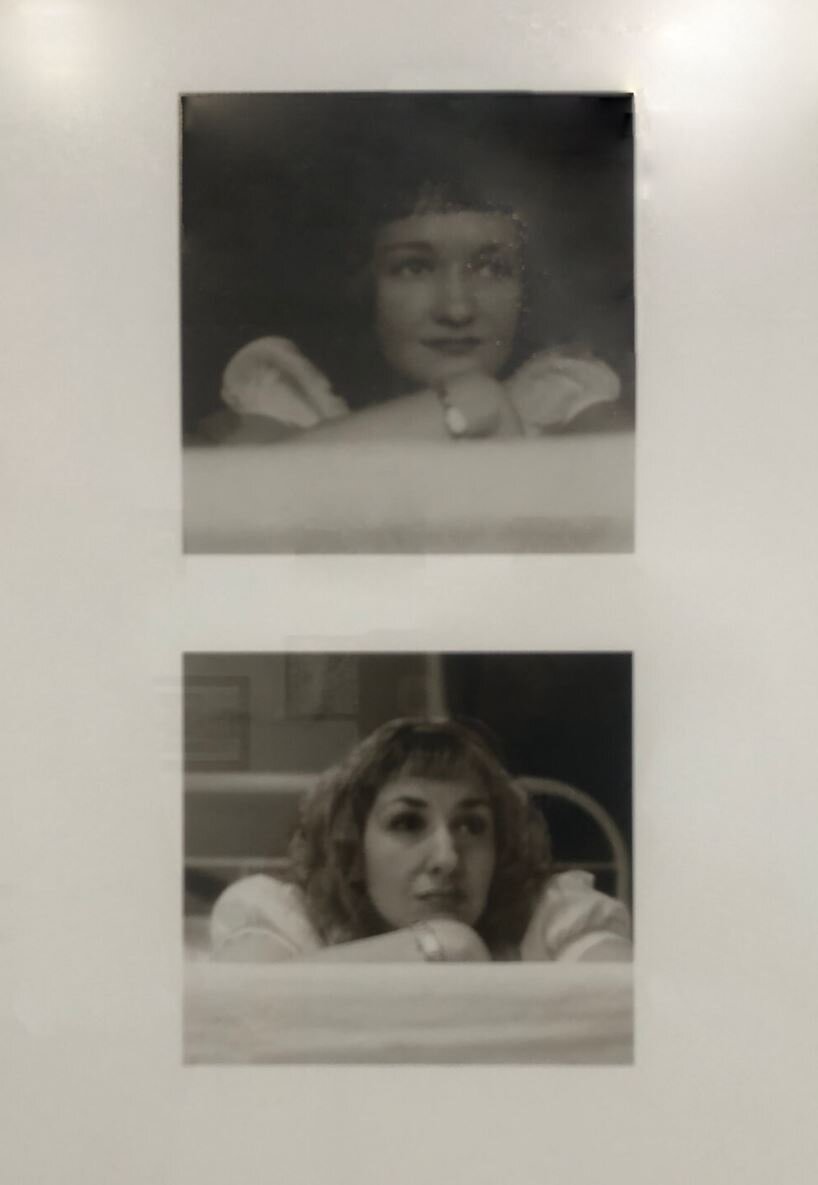

Recapturing Grace, Valerie George

Archival pigment prints, 2003

Inspired by Roland Barthes Camera Lucida, this series explores topics explored in photography theory addressing the notion of “the pose” and “the gaze.” Specifically, George is interested in examining the physical similarities between herself and her mother while also considering what it means to be a woman photographed, to pose for a photograph, and to recreate a photograph.

Aimee Gilmore

Separate Together (Maya’s cord)

Separate Together (Max’s cord)

3d printed plastic, 2021

Milkscape

Breast milk on glass as digital print fabric,

15’ x 18’, 2016

Insiders (orange dog)

Insiders (rainbow dog)

Reversed stuffed animals, 2020

My work reflects the process of archiving an often devalued routine: motherhood, and accentuate my innate desire to cling to both the materials and objects that emphasize the necessity of letting go. My practice highlights the communication between mother and child through archiving the abstraction and sentimentality of my daily rituals. By focusing on the labor of motherhood, as emphasized through the collection of familiar objects and imagery, I begin to viscerally relate the abstract nature of motherhood to the unpredictable nature of art- making. I seek a more thorough and vivid understanding of my own labor as mother by making works from the generative processes of my own body. Time is different as a mother. I try to re-imagine the first few days or weeks or even months in this role, but it feels almost dreamlike. I cling to the now discarded objects, the relics of their smallness. I save them, I honor them, I cut them apart, I put them back together, I coat them, I encapsulate them. I line them up proudly like trophies; awarding myself the permission to long for the times I once prayed would go by faster; monuments to motherhood.

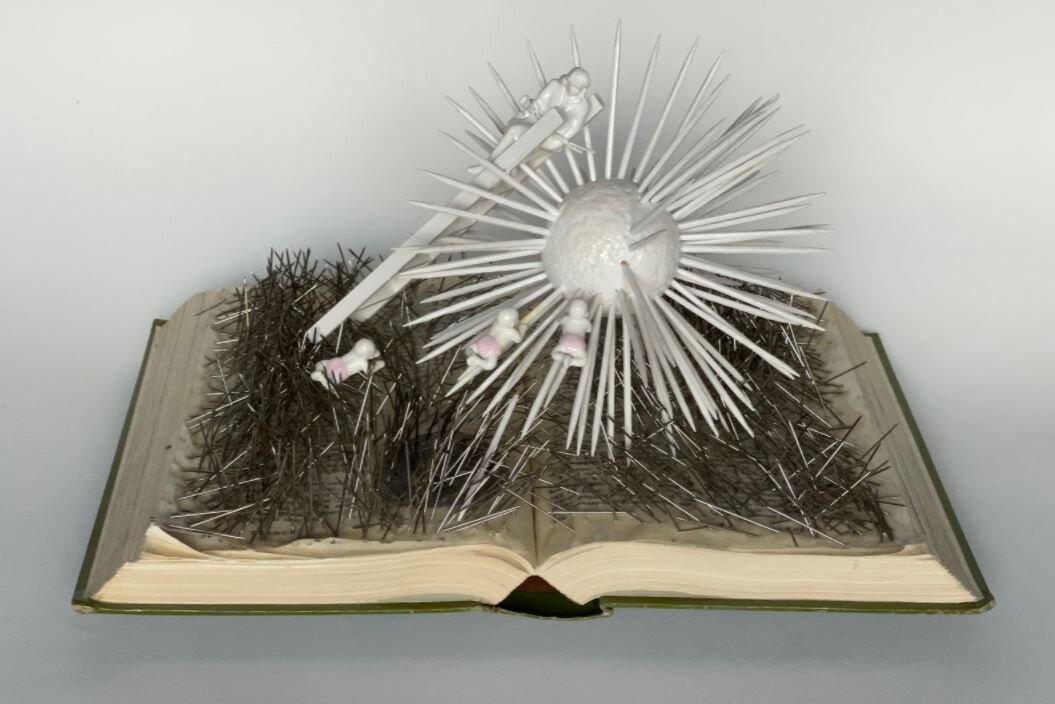

Sarika Goulatia

Girl Child, Thinking About Female Infanticide

Girl child-How to conceive a baby boy?, 6”x6”x8”

Girl child-Tradition of patrilineal inheritance?, 6”x6”x8”

Girl child-Voicing the voiceless?, 6”x6”x8”

How will I raise my girl child?, 5.5”x7”x7”

Listen. I’m speaking, 8.5”x12.5”x8”

What to expect when you are expecting a girl child, 14”X 9.5”

Joyce Kozloff and Fran Flaherty

Nicaragua, Korea, Peru, Afghanistan

Cuba, El Salvador, Congo, Laos

Kuwait, Iraq, Libya, Sudan

Vietnam, Kosovo, Bosnia, Serbia

Cambodia, Grenada

Digital Image Projections, 2020

By the 1990s, maps had become the foundation for my private work, structures into which I could insert a range of issues, particularly the role of cartography in human knowledge. My map and globe works – frescoes, books, paintings, sculptures - which image both physical and mental terrain, employ mutations to raise geopolitical issues. Often their figurations are hybrids, places known only in the imagination, composed of memories and fragments. With an increasing urgency, and moving from earlier, visionary to modern charting as impetus, I seek the physical corollaries between mapping, naming, and subjugation.

During a year at the American Academy in Rome (1999-2000), I created Targets, a 9’ diameter walk-in globe, painted with aerial maps of all the places bombed by the US between 1945 and 2000. There is a disorienting echo inside, so that visitors’ voices are amplified, dramatizing my concern about the barbarity of aerial warfare and vulnerability of civilian populations. Several years later, I developed a large installation piece, Voyages, which included Targets, 65 carnival masks inscribed with maps, and hanging cartographic banners. Together, they examine the history of navigation and western expansion. More recently, I worked with antique cosmological charts of the heavens and terrestrial maps of the earth, overlaid with galaxies and the tracks of satellites found on the Internet. Frightened of future wars in space, I am also drawn into its vast unknown, which today’s astronomers are charting.

In 2011-2012, I completed “JEEZ,” a 12’ x 12’ painting based on the Ebstorf map, a 13th - century circular mappa mundi. It depicted Biblical stories alongside pagan myths within a vision of the world as it was then known. Christ’s body served as a symbolic and literal frame. I drew upon a wide range of artistic practices, incorporating 125 images of Christ from worldwide sources. Archetypal figures accumulate, morphing from holy portraits into a rogue’s gallery of mismatched characters. Its companion, “The Tempest,” was completed in 2014, a 10’ x 10’ work based on a Chinese 18th century world map, in which the Great Wall traverses the upper levels and turbulent seas surround the land mass. Applied to the surface, there are collaged excerpts from more than 40 years of my own art, as well as 3D mini-globes (earrings, ashtrays, erasers, napkin holders, piggy banks, key chains, paper weights, pencil sharpeners, salt and pepper shakers, and yoyos), a merging of seriousness with pop culture. These two pieces together explore eastern and western systems for representing the world….

And then I discovered a cache of my childhood drawings at my parents’ home, created between ages 9-11, which escorted me much further back in time. I incorporated these drawings, many of which are cartographic, into paintings of early maps. From their different stages of life, the young girl and the adult woman began to shift back and forth within the pictorial space. I’d also retrieved my childhood doll collection, and some of those toys found their way into the work, parading along shallow stage-like platforms. Later, I began copying entire childhood drawings directly onto smaller canvases, creating enclosed, subsidiary works excerpted and reinterpreted from the first series. The worldview of my naïve public school pictures is that of early 1950s America. The mindset is further away from me today than the places were then, but my conventional grammar school innocence feels weirdly relevant to me - within our polarized society, where so many people hold onto fantasies about recovering an imaginary past.

I luxuriate in the sheer beauty of maps, as incised diagram and reflection of our world. Co-existing social concerns have been with me from my beginnings as a young feminist artist: how to create an art that is both graphically satisfying and intellectually questioning.

Master Copy (Diptych), Olga Brindar, Paintings, 2020

Reimagining the idea of the master copy -- the study of a classical artist’s painting in order to gain insight into technique -- Master Copy (Diptych) is an empirical study of my 14-month-old daughter’s a priori artmaking. By attempting to understand her intuitive process through the imitation of her work, I am in a sense attempting to unlearn my own art knowledge.

Things I tell my daughter that I need to remind myself, Jessica Gaynelle Moss, 3D Sculpture, 2020

Situated in the corner, previously deemed a site of disciplinary action for children, ‘Things I tell my daughter that I need to remind myself’ offers a moment of relief, support and reflection for mothers. The open chair invites any mother to take a seat and meditate on a guiding principle that they might have offered to their own child that they could benefit from receiving themselves: Get Your Balance, Slow Down, Take Your Time, It’s Okay To Cry, Just Get Back Up.

My People, Christen Russo, Installation: 2D print, 2020

My People

I find comfort in knowing:

in my lineage, mamas and papas

scrunched their noses,

shook their legs after sitting down too long,

roared out happiness, squeezed my

grandmothers so tight they

protested the love -

Yes, yes,

the same

grandmothers who enveloped my mothers,

who folded themselves

around

my

selves,

who reached their fingers down as I do,

so you could grab on and perform my steps,

your feet floating in dance.

Abscission, Lindsey Peck Scherloum

Video, 2020

In a 21st century western culture where motherhood has transformed in response to our now traditional habit of living separate from our families, google searches provide the advice our parents and siblings once shared, and video messages and FaceTime offer the engagement relatives and friends once had on a regular physical basis.

It is easy to be alone, stay in the house all day with the baby, delight in watching her, laud my own simple accomplishments at parenting, mesmerized the way I am watching a fire. I take videos to send my my parents, to her great grandmother, but I get distracted and forget until I spend hours watching them months later. It is easy to turn inward, to revel in this world of two, down to the thin curved lines drawn between our bodies, and meditate on the thinness of our skin now permanently separating us as two.

This new work, Abscission, is my latest exploration into the female form, dating from a year ago when I entered motherhood and began documenting that intimacy of two bodies, mother and child, in their early metaphysical separation. Abscission is the shedding of a part of the body, like a leaf from a tree, or a the petals of a flower, and on a cellular level is the final step of cell division, the moment when the membrane dividing a cell in two separates into equal parts, and each daughter cell is its own entity.

This video form of Abscission is a series of very close abstracted portraits taken in the secret maternal moments of skin to skin and shown in slow motion, juxtaposed against a barrage of images documenting the lonely gaze of a new mother and the slow metaphysical separation. These sequences also point to the iPhone as a tool to memorialize this solitary experience, and connect with others. The segments alternate back and forth creating a rhythm, moments of slow breath and calm amid the frenetic flood of images that repeatedly span birth to one year in a matter o of seconds. The video is approximately 5 minutes long, and intended to be projected on a loop. A short section can be seen here: https://vimeo.com/394581951/c376cc2eae

The full Abscission video piece can be viewed in person at the McDonough Museum of Art.

Le Jardin de L'amour de ma Granmere, Nancy Lewis-Shell

Acrylic on canvas, 8” x 10”, 2018

This is a picture of my grandmother Nannie Lu Louis She was born in the late 1800’s in the post civil war segregated south. Nannie Lu dressed in black dresses with lace collars. She had such a face that she could be anyone’s grandmother. Grandma kept a wonderful exotic garden in her city backyard where she grew vegetables and flowers. I painted her in her garden. Being with her was like being from another time and place. But her past was so frightful she rarely spoke of it. I learned about it one day because I was studying my French lesson.

“Granny,” I asked, “Why do you keep repeating what I am saying?” I was annoyed.

“Because you keep asking me how am I doing and I told you I am okay.” Then the story came out how she was the biracial daughter of the plantation owner and her mother. The plantation owner’s wife hated her and would beat her if she did not speak French in the house to keep the pretense that she was merely a ladies’ maid and not his daughter. My grandmother had a second grade education but she could speak fluent French. Here I was in high school stumbling over the language that she could have taught me.

My grandmother was not bitter about her past. She was a very spiritual lady. She taught me about what Philadelphia looked like in 1916 before the influenza epidemic broke out. She was a female minister when female ministers were not respected. She taught me that Love never fails you. I always felt her love and care by the wonderful food she prepared with her magic apron from her garden. She was a saint to me. This picture hung at the Barnes Foundation and was a finalist in the let’s Connect Contest.

Scarecrow, Sarah Simmons

3D sculpture: rake, flowers, plastic doilies, paint, dictionary pages, text, altered dress, 2018

The way words are used- intentionally, deliberately, accidentally, impact the receiver of these words in extreme ways. Like our natural environment, words can nurture, and words can destroy. I use discarded materials because they contain a multitude of stories to tell from their rich and varied histories, as well as being more environmentally friendly.

I use text in my sculptures to investigate ways we communicate with written language. I transform discarded materials in unexpected ways, creating work that appears superfluous and pretty, but upon further examination carries serious and deliberate meaning.

Hands Between Mother and Daughter, Grace Wong

Lenticular Print, 2020

American Landscapes, Grace Wong

Mixed media collage, 2020

Hands Between Mother and Daughter and American Landscapes describe the fraught notion of care within my family, a love language which has been muddled in the face of a generational and migratory shift, but nevertheless strong. Hands Between Mother and Daughter is a lenticular print that oscillates between my hands and my mothers hands, as I search for a connection between me and my mother. American Landscapes is collage featuring a photo of me embracing my late grandfather, a memory which I do not recollect.